The date is October 29, 2018, and Britain faces its darkest hour. On the battlefields of Europe, and the Armed Forces have been humiliated.

In makeshift prison camps on the continent, thousands of young men and women sit forlornly, testament to the collapse of our ambitions.

From the killing grounds of Belgium to the scarred streets of Athens, a continent continues to bleed. And, in the east, the Russian bear inexorably tightens its grip, an old empire rising from the wreckage of the European dream.

Yesterday, after a run of military defeats unequalled in history, the British Prime Minister offered his resignation. There is talk of a National Government, but no one has any illusions of another Churchill waiting in the wings.

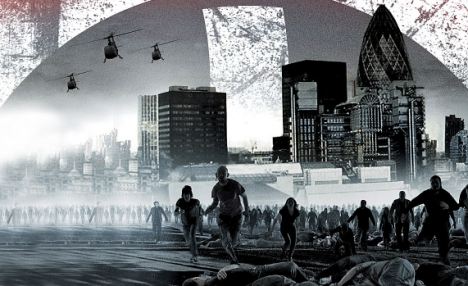

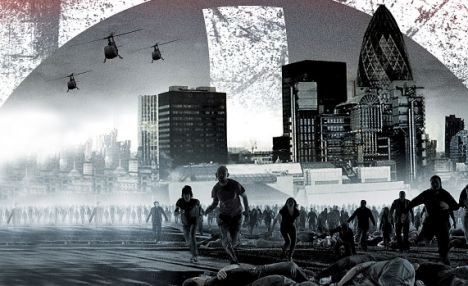

And all the time, across the Channel, enemy forces make their final preparations for the inevitable invasion. Some talk of surrender; no one speaks of victory. Less than ten years ago, millions still believed in a peaceful, united Europe. How did it come to this?

When future historians look back on our humiliation, they will surely judge that the turning point was the last week in October 2011.

Largely forgotten today, the main event was yet another interminable European summit in Brussels — the 14th attempt to ‘save the euro’ in just 20 months.

Largely forgotten today, the main event was yet another interminable European summit in Brussels — the 14th attempt to ‘save the euro’ in just 20 months.

Hoping to secure German support for a massive one trillion euro rescue package, Chancellor Angela Merkel gave her parliamentarians a chillingly prescient warning.

‘No one should believe that another half century of peace in Europe is a given — it’s not,’ she said.

‘So I say again: if the euro collapses, Europe collapses. That can’t happen.’

At the time, many observers scoffed that she was being absurdly melodramatic. But, seven years on, no one is laughing.

What Mrs Merkel had grasped — and what many European leaders refused to recognise — was that the Continent was threatened by a toxic combination of spiralling debt, economic recession, surging anarchism and a pervasive collapse of confidence in capitalism itself.

That week, even St Paul’s Cathedral in London — whose survival had been a memorable symbol of British defiance during the last European war — was shut down by anti-capitalist protesters.

At the time it seemed a tiny, even trivial incident. But it was merely a taste of what was coming.

For by February 2012, it was terrifyingly obvious that the latest eurozone package had failed. In Greece, protests against the government’s austerity measures had turned into daily running battles, while much of Western Europe had now sunk back into recession.

A month later, after an angry mob had invaded the Greek parliament itself, Greece announced it was withdrawing from the euro. Almost overnight, the European markets were hit by the biggest losses in financial history.

As law and order collapsed on the streets of Athens, France and Germany sent in 5,000 ‘peacekeepers’ to restore calm. But when they came under attack from petrol-bomb throwing demonstrators, it was clear that more drastic action might be needed.

Meanwhile, the Greek collapse was sending shockwaves across Europe.

With the markets turning their attention to Italy, and Silvio Berlusconi’s beleaguered government struggling to maintain order, Europe’s fifth largest economy was suddenly at risk.

In the summer of 2012, massive anti-capitalist demonstrations in major Italian cities turned into outright rebellion. And when Berlusconi sent in the army to maintain order, the first bombs began exploding in the banks of Rome, Milan and Turin.

Anti-capitalism had caught the imagination of a generation. And the bomb alert at the Bank of England —when the entire City had to be evacuated after warnings from the so-called ‘Guy Fawkes Anti-Cuts Collective’ — was merely the first of many.

In July 2012, three people were killed by a bank bomb in Frankfurt. A month later, 15 people were killed in Dublin. And in September, in tragic events that will never be forgotten, 36 people were killed by explosions across the City of London.

By now demonstrations and riots were fixtures on the evening news. And as Germany and France struggled to keep the eurozone alive, there were the first signs of a disturbing new authoritarianism.

In Italy, where the Berlusconi government had declared a permanent state of emergency, some cities had degenerated into virtual civil war.

And when Berlusconi formally requested assistance from his European partners, the French president Nicolas Sarkozy — who had narrowly won re-election earlier that year — was only too keen to flex his muscles.

By the end of 2012, there were an estimated 15,000 French troops on the streets of northern Italy — as well as a further 14,000 ‘European peacekeepers’ in Athens and Thessaloniki. Slowly but surely, the continent was sliding towards armed confrontation.

By the following year, a peaceful settlement to the implosion of the European Union seemed increasingly unlikely.

The last major Brussels summit, in March 2013, broke up acrimoniously when many smaller European nations refused to accept Germany’s demands for greater fiscal austerity and economic integration.

With alarming speed, the threads of peaceful unity were unravelling.

With the European economy heading into depression, nationalist movements were gaining support across the Continent. Skinheads were on the march; in cities from Madrid to Budapest, foreigners and immigrants were the victims of violent abuse.

At another time, the terrible Spanish riots in the spring of 2014, when 63 people were killed in a shocking outbreak of arson and looting, would have dominated the headlines.

But most people’s attention was focused further east. No country had been hit harder by the financial crisis than little Latvia, which by 2014 had an unemployment rate of more than 35 per cent. And with almost one in three of its citizens being ethnic Russians, economic frustration soon turned into nationalist confrontation.

On August 12, 2015, after days of fighting on the streets of Riga, the Russian army rumbled across the border. The Russians had come to ‘restore order’, Vladimir Putin assured the world.

But his statement to the Russian people told a different story.

‘Europe’s crisis is Russia’s opportunity,’ Putin announced. ‘The days of humiliation are over; our empire will be restored.’

Once, the West would have come to Latvia’s aid. It was, after all, a member of both the European Union and of Nato — though the new American isolationism meant that Nato membership was effectively worthless.

But since French troops were already committed to Greece and Italy, Paris refused to intervene.

And in London, the new Prime Minister, Ed Miliband, assured the nation that he would never commit British troops to help ‘a faraway country of which we know nothing’.

In Moscow, the message was clear. Six months later, Russian ‘peacekeepers’ crossed the border into Estonia, and in March 2016, Putin’s army occupied Lithuania, Belarus and Moldova.

When Brussels complained, the Kremlin pointed out that European peacekeepers were already on the streets of Athens, Rome and Madrid. Why, Putin asked, should the rules be any different in the east?

And, indeed, he had a point. Even in Paris, there was chilling evidence of a slide towards ruthless suppression of civil dissent — justified as a short-term measure to check the rise of anti-capitalist terrorism.

That summer, Sarkozy amended the French constitution so that he could seek a third term, claiming that stability mattered more than legal niceties. Now more than ever he seemed to see himself as the reincarnation of Napoleon Bonaparte, ostentatiously tucking his hand into his military-style greatcoat.

Back in October 2011, he had told David Cameron to ‘shut up’, claiming that Europe had ‘had enough’ of British advice. Now he seemed to have tipped over into outright Anglophobia.

The crisis had been ‘made in London’, Sarkozy told French television in August 2016.

‘But Britain’s day is done. The future lies in a Russian east and a European — that is to say, French — west.’

For some British newspapers, his words were proof of an unspoken alliance between Moscow and Paris, sweetened with Russian oil and gas money. And, by now, Napoleonic ambitions seemed to have gone to the French president’s head.

Five days before Christmas 2016, Sarkozy told a cheering crowd in Vichy that ‘all European Union members must fully embrace our project and join the euro, or they will pay the price’.

In Britain, his remarks provoked a storm of outrage. Many insiders suggested that left to his own devices, Ed Miliband would have been more than happy to join the euro.

But, by now, the weak Prime Minister was almost completely ruled by his overweening Chancellor, Ed Balls, who insisted that Britain simply could not afford to join a patently unfair Franco-German currency.

As France tightened the pressure, with French farmers ritually burning British imports outside the Channel ports, Miliband cracked, handing in his resignation and scuttling off to take up a teaching post at Harvard.

In a desperate attempt to reinvigorate Labour’s popularity, Ed Balls announced that he was opening talks on British secession from the European Union — even though France and Germany insisted that they would block this ‘illegal nationalist piracy’. But now events across the Channel took a bloody and decisive twist.

For years, Belgium had been crippled by antagonism between Dutch-speaking Flemings and French-speaking Walloons.

The country had not even had a proper government since the summer of 2010, being run first by a caretaker coalition and then, from 2014, by the European Union itself. But in the summer of 2017 inter-community rioting in the centre of Brussels became terrifyingly brutal.

From Wallonia, there came reports of Dutch speakers being beaten and intimidated out of their homes. On August 1, Sarkozy sent in French paratroopers.

‘Brussels is the very heart of Europe,’ he said. ‘Which is to say, it is properly part of France.’

For Britain, this was the final provocation. All parties agreed that, thanks to Britain’s long-standing pledge to defend Belgian independence, we had no choice but to dispatch peacekeepers of our own.

The events of the next few months make sorry reading. Even in 2011, Britain had only 101,000 regular soldiers to France’s 123,000, but years of swingeing spending cuts had taken their toll.

By 2017, Britain’s land forces were down to just 75,000. And when fighting broke out between French and British peacekeepers in the outskirts of Ghent, no one seriously doubted that the French would win.

So it is that, a year later, we find ourselves at our lowest ebb. Aided by Spanish and Italian auxiliaries, backed by German money and quietly supported by neo-imperialist Russia, the French army has encircled our expeditionary force on the other side of the Channel and cut it to shreds.

The Americans have deserted us, while every week brings fresh anti-war and anti-capitalist riots in our cities. The shelves are increasingly empty; national morale has hit rock bottom.

In Scotland, polls show that more than 70 per cent want independence; in Northern Ireland, the bombs of the Real IRA explode almost daily.

Last week, addressing a vast crowd in French-occupied Brussels, Nicolas Sarkozy declared that it was ‘time to extinguish the stain of Waterloo’.

‘Britain has always been part of Europe — even if they have refused to recognise it,’ he said.

‘It is time to welcome them into our family — by force, if necessary.’

A few diehards talk of fighting in the last ditch. But no one seriously believes that Britain can hold out for long.

The Union flag hangs tattered and forlorn; our days of glory are long gone. And, in Brussels, our new masters are preparing for victory.

Even now, the transformation in our fortunes seems almost incredible.

Seven years ago, Angela Merkel’s talk of the threat to peace seemed implausible, even absurd.

What a tragedy that we did not listen when we still had a chance.

Source: DailyMail